A response to How to Make Art That Withstands the Test of Time by Alexandra Ossola in Facts So Romantic, on Nautilus.

It was a dark and stormy night, and all of the sculptures deteriorated.

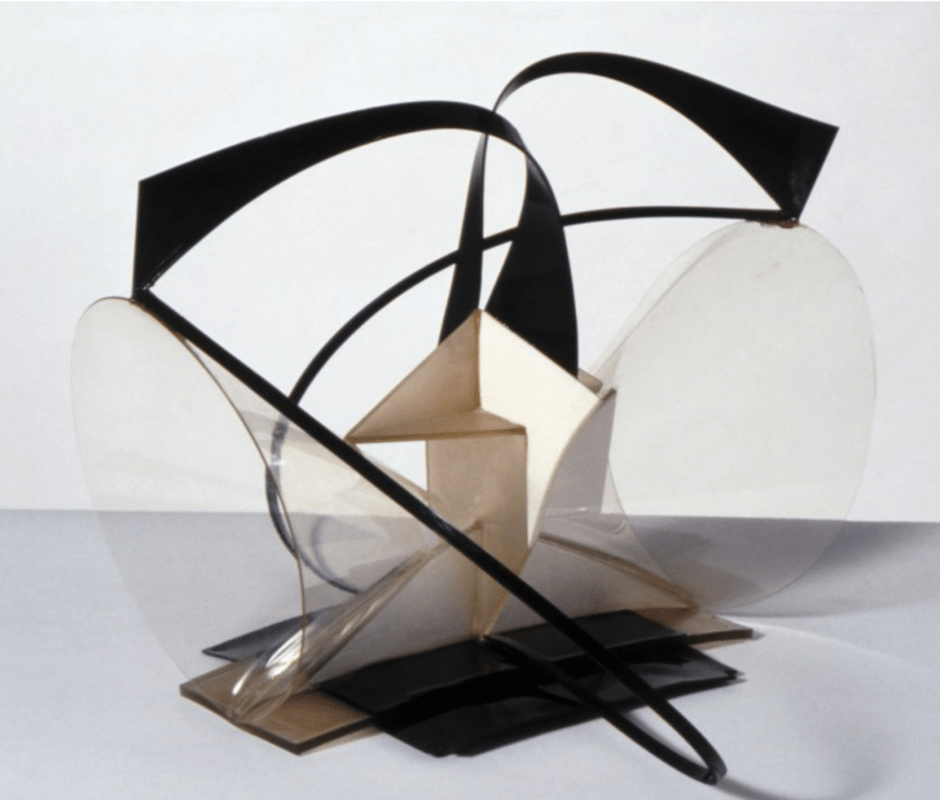

The basic premise of Ossola’s article is ensuring the longevity of artwork when made with either experimental or traditional materials, if that is the intention of the artist. The material with which the 1930s sculpture artist Naum Gabo was working, celluloid, turned out (unbeknownst to him at the time of creation) to be highly unstable. As a result, less than 30 years later, his sculptures began degrading beyond repair, so he created a copy, which has met a similar fate. The “failure” in this situation lies both with the artist and his lack of knowledge regarding the stability of his chosen medium, and that of the initial conservator in how to preserve the work.

The consequences of deterioration for the museum and private owners of Gabo’s works is lost value. On the one hand, those who thought they had purchased or acquired a permanent piece of valuable art are now faced with its potential destruction or disappearance, as well as the loss of revenue; one wonders if they would have purchased it knowing this. On the other, those of us who have not seen Gabo’s structures may never have the chance to, so their innate value as a piece of art to be viewed is also lost.

If we are to assume that Gabo wanted his pieces to last in their original state, the initial 1930s conservators, and each subsequent conservator who received the sculptures, should have done a good deal of research to determine how to best preserve the material. When presented with the item, its conservators should have set up the environment to support its exhibition. If they discovered that indeed there was nothing they could do to prevent the piece’s demise, this could have been indicated as part of the exhibit. For example:

Due to the unstable nature of the materials, this artwork is in the process of breaking down, and will eventually disappear. You can see evidence of this in the way that the plastic has bent and cracked. This is an unintended result of the artist in his selection of materials.

The piece may be viewed as even more valuable, because its existence is limited.

Artists interested in experimenting with alternative or unique materials to achieve a certain effect may be more concerned with the outcome than with the ability of the work to endure indefinitely. Whether or not a piece is intended to be permanent or ephemeral is a consideration when conservators and curators enter into a relationship with an artist and/or an artwork, so conservation efforts made to concretize works must be guided by specific direction from the artist for their maintenance.

It is difficult to define what to capture with intentionally ephemeral works, such as performance art, where photographs, video, or memory are the only methods for memorializing a piece. Here again, collaboration between conservator and artist helps to identify what constitutes the artwork to be captured: The part that a majority of the viewers are present for; a particular moment in the work; the entirety of the work, seen or unseen by the public; or the reperformance or recreation of the original. For example, when examining a work such as Marina Abramovic’s “The Artist is Present,” we can not be sure what is considered to be the work, so we must have guidance from the artist in what to capture. Is it the entirety of the # of days she was sitting, or one experience with an individual? Is it her experience, the viewer’s experience, the two experiences together? Has the documentary made about the work done a sufficient job of capturing it, or is the documentary an adjunct to other conservation efforts?

Similarly, there is difficulty in identifying what to conserve when faced with Richard Serra’s large iron pieces, “Matter of Time” at the Guggenheim in Bilbao. They are constantly changing. When initially brought into the space the sculptures were a bright, even, orange color. Now, due to the material’s interaction with humidity caused by the environment, visitors’ breath, and bodies touching the works (even though they’ve been instructed not to), the color of the sculptures have changed over time to a mixture of streaky rust-brown, orange, and black. Serra’s intentions must be made clear to conservators, indicating if these changes are part of the work or if conservators should have done something to maintain the original color and state of the pristine originals, rolled into the space on day one. (NB: I think art permanence will be a topic for another exploration.)

Gregory Smith, senior conservation scientist at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, stated that it is the artist’s job to create the art, and the conservator’s job to “make it last.” In some cases, such as Gabo’s, it simply isn’t possible, and in other cases, the responsibility of the conservator in the collaboration is to ask if they should be trying to.

Gabo: © Nina and Graham Williams

Abramovic : Ruth Fremson/The New York Times

Serra: https://www.guggenheim.org/about-the-collection